Champagne grape varieties

The nature of the terroir guided the selection of the most suitable grape varieties. Pinot noir (black grape), pinot meunier (black grape) and chardonnay (white grape) are by far most commonly used today. Arbane, petit meslier, pinot blanc and pinot gris (all with white grapes), which are also authorised, represent less than 0.3% of the vineyard.

Le Pinot Meunier: Approximately 32% of the vineyard planted

Le Pinot Noir: Approximately 38% of the Champagne vineyard

Le Chardonnay: Approximately 30% of the surface area

From harvest to press

As soon as they arrive at the pressing facility, the grapes are weighed and recorded in a register. Pressing results in the keeping of a press book to identify each “marc” (load of a press representing 4000 kg of grapes), vintage by vintage and grape variety by grape variety, kept by the winegrower or sold to a house. The minimum alcoholic strength fixed for the harvest is also checked.

The production of a white wine, when two thirds of the available grapes are black-skinned, requires compliance with five main principles:

- pressing immediately after picking,

- pressing of whole bunches,

- smooth and progressive control of the pressing process,

- low extraction efficiency,

- splitting of the juices on leaving the press.

Preserving the distinctive character of the vintages

Each vintage arriving at the pressing facility is identified according to the date and time of harvest. They are pressed separately so that their origin is as traceable as possible. To do this, homogenous “marcs” are created: same grape variety, same plot or grouping of comparable plots.

The extraction of grape juice, the “cuvée” and the “taille”

Only 25.50 hectolitres of must can be extracted from a 4000 kg “marc”, the traditional pressing unit. The pressing is split by separating the first extracted juice, 20.50 hl which constitutes the “cuvée”, from the next 5 hl, called “taille”. The musts have very specific analytical characteristics. The “cuvée”, which represents the purest juice from the pulp rich in sugar and acids (tartaric and malic), gives wines of great finesse, with subtle aromas with a good freshness in the mouth and a better aptitude for ageing. The “taille”, also rich in sugar with less acidity but more mineral salts (potassium in particular) and colouring matter, produces wines with intense aromatic characters, fruitier when young, but with less longevity.

Setting of the musts before racking

As the juice is extracted, it flows into open tanks (known locally as “belons”) where it is treated with sulphites (sulphur dioxide or SO2) at the rate of 6-10g/hl depending on the varietal, the condition of the grapes and the musts in question (whether “cuvée” or “taille”).

Sulphites have antiseptic properties that help to inhibit the growth of moulds and unfriendly indigenous bacteria. Their antioxidant action safeguards the physicochemical and sensory quality of the wines.

“Débourbage” is the settling of the freshly pressed grape juice prior to fermentation, so as to produce wines with the purest expression of fruit.

“Débourbage” (literally “de-sludging”) is a static settling process. In the first few hours, flocculation occurs thanks to the enzymes naturally present in the juice or added. The solids (particles of skin, pips, etc.) settle to the bottom of the juice. After 12-24 hours, the clear juices are drawn off.

After racking, the clarified juice is transferred to the fermentation room to begin the winemaking process.

Primary fermentation :

Primary (alcoholic) fermentation is the starting point for each individual style of wine.

An array of winemaking methods to suit different target styles.

The actual winemaking approach depends on the winemaker, who is looking to produce a wine with a particular style, quality and aging potential.

Primary fermentation

The primary, or alcoholic, fermentation of Champagne wines is the process that transforms the grape musts into wine: the yeast consumes the natural grape sugars, producing alcohol and carbon dioxide along with other by-products that contribute to the sensory characteristics of the wine.

Primary fermentation takes place immediately after pressing, usually in stainless steel tanks though some producers still ferment their wines in wood.

Champagne Louis Casters chooses to avoid malolactic fermentation.

Malolactic fermentation is the process that transforms malic acid into lactic acid. It takes place at the end of the alcoholic fermentation. Like all forms of fermentation, malolactic fermentation influences wine aroma development. It is an optional process. Some Champagne makers prefer to avoid it in order to retain freshness as well as the floral and fruity aromas of the grapes. But most prefer to use the process to create softer, riper and generally creamier sensations.

Final stage: clarification

We clarify our wines kieselguhr filtration (cold treatment). With the lees and other impurities eliminated, these base wines are known locally as “vins clairs”. Base wines are classified by varietal, vintage, vineyard (or sometimes the individual vineyard plot) and pressing fraction (whether “cuvée” or “taille”), they are ready for blending as a “cuvée” (local term for blended Champagne).

The blending of Champagne wines

The blending process at the heart of Champagne winemaking plays on the diversity of nature, combining wines from different crus, different grape varieties and different years.

Blending wines with different characteristics

There are so many subtle differences between the crus that no two blends are ever the same. The result is an array of wines that capture the multifaceted character of their appellation.

Blending wines from different but complementary grape varieties

Marrying different grape varieties brings contrasting and complementary qualities to Champagne wines.

- The Pinot Noir contributes aromas of red fruits and adds strength and body to the blend.

- The Pinot Meunier contributes supple body and fruity flavours. Its bouquet is intense; it develops more quickly over time and gives the wine roundness.

- The Chardonnay gives the blend finesse. As a young wine, it brings floral notes, sometimes with a mineral edge. It is the slowest to mature of the three Champagne varietals and the longest-lived.

Blending wines from different years

The annual weather variations in Champagne terroir affect the quality of the grapes, making for very different vintages depending on how cold, hot, wet, etc. it was in the year in question.

Whatever its specificity, a blend almost always calls upon the three parameters mentioned above: the terroirs, the grape varieties and the years.

The winemaker may also decide to focus on one dimension in particular.

It is possible to:

- – A vintage Champagne commemorates a truly exceptional year by including no reserve wines at all.

- – A single-varietal Champagne, whether Blanc de Blancs or Blanc de Noirs, celebrates the taste of a single grape variety.

- – A single-vineyard Champagne expresses the distinctive qualities of a single cru, “lieu-dit” (named vineyard plot) or sometimes “clos” (walled vineyard).

Fourth dimension of blending: the winemaker’s talent

Bottling and creating effervescence

Bottle fermentation transforms still wine to sparkling wine – hence the name “prise de mousse” (literally “foam creation”).

The bottling – or “tirage” – cannot take place until 1 January following the harvest.

To kick start the fermentation process, the champagne is seeded with tirage liqueur made up of sugar, leaven and a riddling agent.

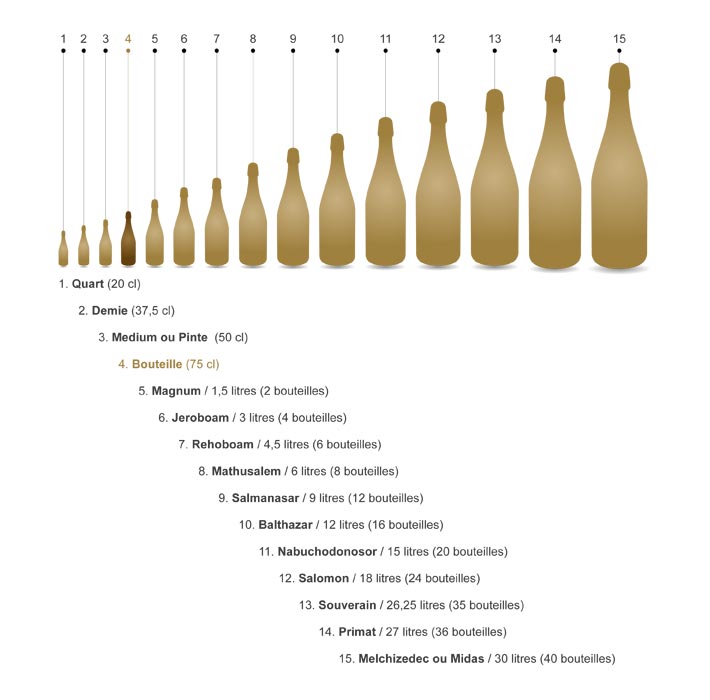

In accordance with the regulations which prohibit “transvasage” – the transferring of the newly effervescent wine from one bottle to another – (from a half-bottle to a jeroboam, for instance). All Champagne wines must be sold in the bottle in which it was made.

The bottling (“tirage”) stopper

Once filled, the bottles are hermetically sealed with a polyethylene stopper known as a ‘bidule’, held in place by a wire cage/metal cap. The bottles are then transferred to the cellar and stacked “sur lattes”: horizontally, row upon row. These days they are mostly stacked in steel crates on a palette. A few producers still use cork for the “tirage” (bottling) stopper.

Inside the bottle, the wine undergoes a second fermentation that continues for 6-8 weeks. The yeasts consume the sugar, releasing alcohol and carbon dioxide, along with esters and other superior alcohols that contribute to the wine’s sensory profile.

Different bottles

Champagne wine is the only one to come in a large variety of bottles, from the most practical to the most festive.

More coming soon…